Executive summary

The Bidoon (also spelt Bidun, Bedoon, Bedun), are a largely stateless Arab minority mostly descended from nomadic tribes known as Bedouin who settled in Kuwait but were not included as citizens at the time of the country’s independence in 1961 or shortly thereafter. All Bidoon in Kuwait are classed as ‘illegal residents’ by the Kuwaiti state, who also allege that Bidoon conceal their ‘true’ nationalities, owing to their aspiration to acquire Kuwaiti citizenship and its associated benefits. Sources estimate there to be between 83,000 to 120,000 Bidoon in Kuwait

The Upper Tribunal (UT) in the country guidance case of BA and Others (heard on 11 June 2003 and promulgated on 15 September 2004) held that the Bidoon are a particular social group under the Refugee Convention.

There have been a number of government committees that have been established in attempts to resolve nationality and status issues of the Bidoon. In 2010, the government created the Central Agency for Remedying Illegal Residents’ Status (CARIRS). This committee regulates the Bidoon population’s access to documents and formal rights.

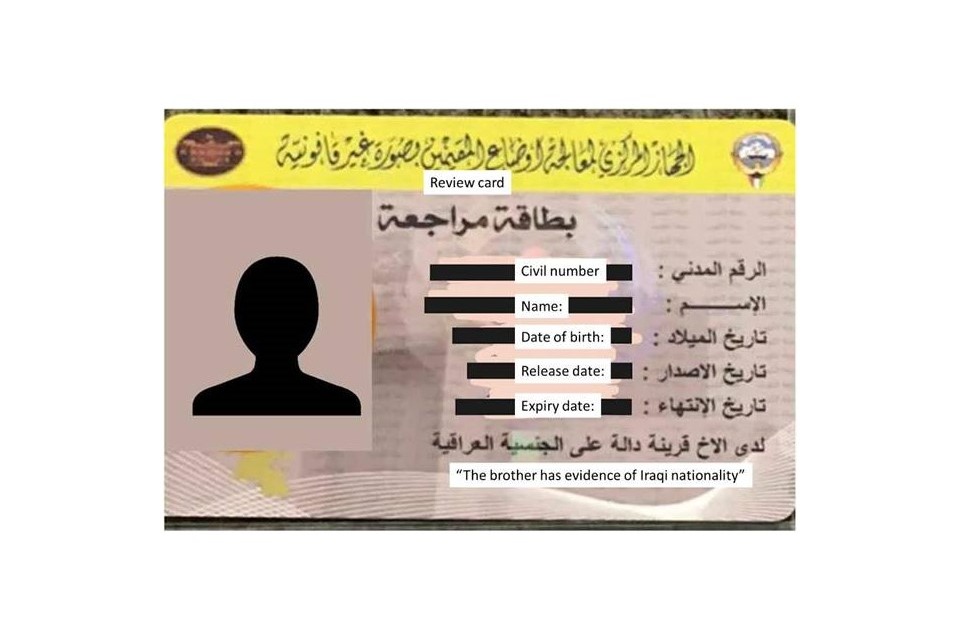

The key piece of documentation that is issued by the CARIRS is the ‘review card’ (also known as ‘security card’). The review card is essential for Bidoon to access primary and secondary education, medical treatment, employment, driving licences, food ration cards and other official documents such as birth, death, and marriage certificates, though some of these services may be accessed without a review card depending on a persons social connections known as “wasta”. Sources describe the process of renewing Review cards as arbitrary and non-transparent. Review cards have been more difficult to renew recently and are issued for shorter periods.

The UT in the country guidance case of NM (documented/undocumented Bidoon: risk) (heard on 14 and 30 January 2013 and promulgated on 24 July 2013) held that the evidence relating to the documented Bidoon does not show that they are at real risk of persecution or breach of their protected human rights. The undocumented Bidoon, however, do face a real risk of persecution and breach of their human rights.

Available country information does not indicate that there are very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence to justify a departure from these findings.

Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from the state they will not, in general, be able to obtain protection from the authorities and are unlikely to be able to internally relocate.

Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

All cases must be considered on their individual facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate they face persecution or serious harm.

Assessment

About the assessment

Section updated: 31 July 2024

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is information in the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

- a person has a well-founded fear of persecution or faces a real risk of serious harm by the state because they are a Bidoon (a stateless Arab).

- the state (or quasi state bodies) can provide effective protection

- internal relocation is possible to avoid persecution/serious harm

- if a claim is refused, it is likely to be certified as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1. Credibility

1.1.1. For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2. Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3. Decision makers must also consider making an international biometric data- sharing check (see Biometric data-sharing process (Migration 5 biometric data-sharing process)).

1.1.4. Some people may claim to be Bidoon when they are nationals of another country, such as Iraq. They are not usually stateless. Decision makers should consider the need to conduct language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis). Decision makers should also refer to the Statelessness Guidance.

1.1.5. Others have regularised their status in Kuwait by showing evidence of, or successfully applying for, a second nationality. The Kuwaiti Government treats a person in this situation as a legal foreign national. A person in this scenario is not stateless.

1.1.6. Conversely there are Bidoons who have obtained counterfeit foreign passports to try and regularise their status. When trying to renew their review cards they found that the Kuwaiti Authorities had listed them as that foreign nationality and were no longer able to attempt to claim Kuwaiti citizenship, even if registered in the 1965 census. Family members may also find that they have been registered under that foreign nationality. Further issues may arise when trying to renew counterfeit foreign passports. A person in this scenario may be stateless.

1.1.7. In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1. Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

1.2.2. If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3. For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information in this section has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1. Actual or imputed particular social group (PSG).

2.1.2. Establishing a convention reason is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of an actual or imputed Refugee Convention reason.

2.1.3. Bidoon form a particular social group (PSG) in Kuwait within the meaning of the Refugee Convention because they share an innate characteristic or a common background that cannot be changed, or share a characteristic or belief that is so fundamental to identity or conscience that a person should not be forced to renounce it and have a distinct identity in Kuwait because the group is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.

2.1.4. Although Bidoon in Kuwait form a PSG, establishing such membership is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question to be addressed is whether the person has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of their membership of such a group.

2.1.5. In the country guidance case of BA and Others (Bidoon – statelessness – risk of persecution) Kuwait CG [2004] UKIAT 00256 (heard on 11 June 2003 and promulgated on 15 September 2004), the Upper Tribunal held that: ‘Since the Bedoon have a tribal identity and are not simply a collection of (mainly) stateless persons, they […] can also be seen to form a particular social group. Bidoon are a “particular social group” under the Refugee Convention.’ (paragraph 91(v)).

2.1.6. For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1.1. In general, while documented Bidoon may face discrimination, it is not by its nature or repetition, or by an accumulation of measures, likely to amount to persecution. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise.

3.1.2. In general, undocumented Bidoon face treatment that is likely by its nature and repetition, or by an accumulation of measures, to amount to persecution.

3.1.3. In the country guidance case of NM (documented/undocumented Bidoon: risk) Kuwait CG [2013] UKUT 00356(IAC) (heard on 14 and 30 January 2013 and promulgated on 24 July 2013), the Upper Tribunal held that:

‘… [T]he evidence relating to the documented Bidoon does not show that they are at real risk of persecution or breach of their protected human rights. The undocumented Bidoon, however, do face a real risk of persecution and breach of their human rights.

‘The distinction made in previous country guidance in respect of Kuwaiti Bidoon, between those who are documented and those who are undocumented, is maintained, but the relevant crucial document, from possession of which a range of benefits depends, is the security card [review card], rather than the “civil identification documents” referred to in the previous country guidance in HE [2006] UKAIT 00051. To that extent the guidance in HE is amended.’ (paragraphs 100 and 101)

3.1.4. Available country information does not indicate that there are ‘very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence’ to justify a departure from the findings in NM.

3.1.5. The Bidoon are a largely stateless Arab minority in Kuwait who were not included as citizens at the time of the country’s independence in 1961 or shortly thereafter. The current Bidoon population in Kuwait have originated from three different groups:

a. those who claim citizenship under Kuwait’s Nationality Law but whose ancestors failed to apply or lacked the required documentation at the time of Kuwait’s independence. b. former citizens of other Arab states (such as Iraq, Syria and Jordan) and their descendants who came to Kuwait in the 1960s and 1970s to work in Kuwait’s army and police forces. c. persons born to Kuwaiti mothers and Bidoon fathers.

3.1.6. Sources estimate there to be between 83,000 to 120,000 Bidoon in Kuwait (see Who are the Bidoon?).

3.1.7. Kuwaiti nationality is determined by Kuwait’s 1959 Nationality Law. Under Kuwaiti law, a child has the nationality of its father only. Children born to citizen mothers and non-national fathers (such as Bidoons) do not inherit citizenship. Kuwaiti women can apply to pass their nationality on to children only when the father is unknown or has failed to establish legal paternity, when the couple are divorced, or upon the death of a non-national husband. The citizenship awards process does not allow Bidoon to provide any evidence to support their case for naturalisation. The person must instead be put forward for citizenship, on a discretionary basis, by the Ministry of Interior. There is a limit of 4,000 persons being able to obtain citizenship per year. Sources do not provide further information on this process or on what basis people are put forward for citizenship (see Kuwait’s Nationality Law).

3.1.8. In October 2022, the Kuwaiti government released figures stating that between 2011 and 2022, 18,277 people had completed the process of obtaining a nationality. However, according to the source, none of those were afforded Kuwaiti nationality and there was no explanation regarding which nationalities were given, or why. Additionally, no guarantees were given by the Kuwaiti government that the new nationalities would be validated by the corresponding country, and no clarity on the changes in rights and status for these people in Kuwait. No updated information on the numbers of persons who have obtained Kuwaiti (or another country’s) nationality since 2022 could be found in the sources consulted (see Central Agency for Remedying Illegal Residents’ Status (CARIRS)).

3.1.9. All Bidoon in Kuwait are classed as ‘illegal residents’ by the Kuwaiti state, who also allege that Bidoon conceal their ‘true’ nationalities, owing to their aspiration to acquire Kuwaiti citizenship and its associated benefits (see State attitudes towards Bidoons).

3.1.10. Since 1993, there have been a number of government committees that have been established in attempts to resolve nationality and status issues of the Bidoon. In 1996, the Executive Committee for the Affairs of Illegal Residents was set up which required Bidoons to register their claims of nationality between 1996 and 2000 (see State apparatus regarding Bidoons). It was this committee that first issued ‘review cards’ (also known as ‘security cards’) to Bidoon (Review Card). In 2010, the government created the Central Agency for Remedying Illegal Residents’ Status (CARIRS) (also known as the Central Agency for the Remedy of the Situation of Illegal Residents, the Central System or the Central Agency). This committee reportedly regulates the Bidoon population’s access to documents and formal rights (see Central Agency for Remedying Illegal Residents’ Status (CARIRS)).

3.1.11. The key piece of documentation that is issued by the CARIRS is the ‘review card’ (also known as ‘security card’). The review card is essential for Bidoon to access education, medical treatment, employment, driving licences, food ration cards and other official documents such as birth, death, and marriage certificates. Available information presents conflicting accounts regarding review cards. Discrepancies include the colours of these cards, what each colour card means or entitles the holder to, and their validity periods.

However, among these sources, yellow emerges as the most frequently cited colour for the review cards (see Review Card and Access to services and basic rights).

3.1.12. A number of sources describe the processes involved in applying for and renewing a review card as arbitrary, unclear and difficult, with the CARIRS using a number of methods to pressure as many Bidoon as possible to declare their ‘true nationality’, renouncing their claim on Kuwaiti citizenship in the process. Some of these methods include:

- repeated postponements of permissions to access services and requests for additional documentation

- shortening the validity periods of the review cards (they were previously valid for one or 2 years but cards only valid for 3 or 6 months are now becoming more common)

- pressure to sign various types of documents in exchange for a renewed card, including declarations renouncing their claim to citizenship, confirmations of information not divulged to the Agency previously and signing blank pieces of paper (which are then used as a confession of having another nationality)

- arbitrary and unjustified attribution of presumed nationality, which then appears both on the renewed review card and in the database records system.

3.1.13. The time taken to renew a review card varies. However, sources stated that an electronic service for renewing review cards that was introduced in November 2022 can take between 4 and 5 days. Information regarding the processes involved with the online review card renewal could not be found within the sources consulted.

3.1.14. Data regarding the number of review cards that have been issued or renewed is limited. The Times Kuwait, a weekly English language newspaper in Kuwait, noted that 32,767 new review cards were issued between January and June 2023. The estimated population of Bidoon in Kuwait is between 80,000 and 120,000.

3.1.15. Review cards may be declined or revoked for security reasons such as criminality, activism, or there being ‘strong evidence’ that the applicant or holder holds another nationality. Family members of Bidoon with security restrictions may also have difficulty renewing review cards. Sources indicate there was an increase in ‘denationalisation’ and security blocks since the Arab Spring protests in 2011, with a peak in 2014, although there are no comprehensive figures on how many people have been denationalised (see Renewal of review cards and Revocation of (and difficulties faced when attempting to obtain) citizenship).

3.1.16. The documented Bidoon (those who hold a review card), are generally able to access government services, gain public and private sector employment and access healthcare and private education. Available information indicates that a person may be unable to renew their review card because of various forms of administrative hurdles or if they have been found to have previously acquired falsified foreign passports in order to obtain government jobs, birth and / or marriage certificates. Despite having held a review card previously, if an individual is unable to renew their review card, they may become de facto undocumented (see Documentation and Treatment of Bidoon).

3.1.17. Undocumented Bidoon, (those who do not possess a review card), even if they possess other pieces of official documentation, are in general unlikely to be able to access basic services such as education, employment, medical care and civil documents such as birth, marriage or death certificates (see Documentation and Treatment of Bidoon).

3.1.18. The Kuwaiti constitution allows for peaceful assembly and association for citizens. However, this is not extended to Bidoon and other non-citizens. Sources indicate that any political activity by Bidoon is heavily restricted and those who speak out publicly are likely to be subject to adverse attention from the state. There have been reports of torture, ill-treatment, sexual abuse and excessive force against Bidoon while in custody although the scale and extent to which this occurs is unclear (see Bidoon protests and treatment of activists).

3.1.19. For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1. A person who fears the state is unlikely to obtain protection.

4.1.2. For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1. Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution or serious harm from the state, they are unlikely to be able to relocate to escape that risk.

5.1.2. For further guidance on considering internal relocation, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

6. Certification

6.1.1. Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2. For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This section contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

The COI included was published or made publicly available on or before 31 July 2024. Any event taking place or report published after this date will not be included.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Who are the Bidoon?

7.1. History and timeline

7.1.1. Minority Rights Group International (MRG) published a Bidoon profile as part of an undated directory of minorities and indigenous peoples. It stated that ‘Bidoon (short for bidoon jinsiya, meaning “without nationality” in Arabic, and alternately spelt as Bedoon, Bidun and Bedun) are a stateless Arab minority in Kuwait who were not included as citizens at the time of the country’s independence or shortly thereafter.’[footnote 1]

7.1.2. The same source provided a history of the Bidoon which stated:

‘Most Bidoon come from nomadic tribes [known as Bedouin] native to the Arabian Peninsula who were in Kuwait when the country gained independence in 1961. The process of determining who was eligible for citizenship, was set out by the 1959 nationality law [see Kuwait’s Nationality Law] inherently favoured Kuwait’s urban residents and those who were connected to influential tribes or families.

‘… On the other hand, many tribal communities in outlying areas failed to register for citizenship when the law was passed, whether due to lack of awareness or understanding of the new law and its implications, illiteracy, or lack of documentation proving their connection to the territory. The concept of territorially-defined citizenship would also have been a foreign concept to many, as it diverged from traditional tribal understandings of belonging which were defined by allegiance to a leader in a context, moreover, where there continued to be migratory communities for whom the notion of states was unfamiliar.

‘… Consequently, approximately one third of the population of Kuwait at the time did not obtain citizenship and was classified as bidoon jinsiya.’[footnote 2]

7.1.3. MRG also commented:

‘In the first few decades after Kuwait’s independence, being Bidoon carried relatively few disadvantages. Bidoon had access to employment, public education and free healthcare, just as Kuwaiti citizens did. They were also able to register civil marriages and receive other forms of documentation.

‘…From this situation of relatively equal status, Bidoon began to face increased restrictions on their rights from the mid-1980s onwards.

‘…the Kuwaiti government began to view Bidoon as a security threat, particularly as it became known that some incoming refugees and individuals from Iraq wishing to avoid military service and persecution were getting rid of their identity papers and posing as Bidoon.

‘…In 1986, the government changed the status of Bidoon to ‘illegal residents’ and began to strip them of their rights. Large numbers were fired from their jobs, while the community as a whole was excluded from free education, housing and healthcare.

7.1.4. The 2011 report published by Human Rights Watch (HRW) entitled ‘Prisoners of the Past – Kuwaiti Bidun and the Burden of Statelessness’, based on interviews and primary research conducted by HRW and from which many other reports [footnote 3],[footnote 4],[footnote 5],[footnote 6] refer to, stated:

‘Today’s Bidun population originates from three different categories. First, there are those Bidun who claim citizenship under Kuwait’s Nationality Law, but whose ancestors failed to apply or lacked necessary documentation at the time of Kuwait’s independence. Among this group are the descendants of nomadic clans which regularly traversed the borders of modern-day Gulf states but settled permanently in Kuwait prior to independence. This group of Bidun have never held the citizenship of any other country.

‘A second group is composed of former citizens of other Arab states (such as Iraq, Syria, and Jordan), and their descendants, who came to Kuwait in the 1960s and 70s, to work in Kuwait’s army and police forces. The Kuwaiti government preferred to register them as Bidun rather than to reveal this politically- sensitive recruitment policy. Some of these migrants settled in Kuwait with their families and never left.

‘The third category of Bidun is composed of individuals born to Kuwaiti mothers and Bidun fathers.’[footnote 7]

7.1.5. Below is a timeline compiled using various sources highlighting important events affecting Bidoons in the years since the nationality law was introduced:

1959 – The nationality laws define categories of Kuwaiti nationality and a range of criteria and limitations[footnote 8].

1979-1981 – Following increased regional tensions due to the Iranian revolution and the Iran/Iraq war, the Kuwaiti government began to view Bidoon as a security threat[footnote 9].

1985 – An assassination attempt on the then-Amir [emir – monarch and head of state] was a turning point as, despite Islamic Jihad Organisation taking responsibility for the attempt, Kuwait blamed a faction of the Bidoon community [footnote 10].

1985-1986 – Following the assassination attempt, Amiri Decree 41/1987 officially reclassified Bidoon from ‘Bedouins of Kuwait’ to ‘Illegal Residents’, stripping them of previous access to state services and benefits of any kind[footnote 11]. A number of Bidoon were reportedly expelled. Large numbers were fired from their jobs, while the community as a whole was excluded from free education, housing and healthcare[footnote 12].

1988 – An appeal court ruled that as no other state considered them nationals, they could not be considered “aliens” in terms of the law. The government ignored the ruling and continued, reportedly, to deport members of the Bidoon community[footnote 13].

1990 – Iraq invasion of Kuwait. The number of Bidoon in Kuwait prior to the war was estimated to be around 250,000. However, many fled during the war and were denied re-entry into Kuwait when the war ended[footnote 14].

Approximately 10,000 Bidoon were deported[footnote 15].

1991 – Post war figures estimate the number of Bidoons in Kuwait to be 125,000[footnote 16].

1993 – The Central Committee to Resolve the Status of Illegal Residents was established to regularise the status of the Bidoon. The Central Committee concluded its work on 26 March 1996[footnote 17].

1996 – The Executive Committee for Illegal Residents’ Affairs (ECIR) was established to process all those who claimed to be illegal residents (Bidoons).[footnote 18].

2000 – Law passed permitting naturalisation of individuals registered in the 1965 census and their descendants, limited to 2,000 per year, which has never been met[footnote 19].

2005-2008 – 3,346 Bidoon granted citizenship[footnote 20].

2010 – November – the Central System to Resolve Illegal Residents’ Status was established and is the current administrative body responsible for reviewing Bidoon claims to nationality[footnote 21]. The Committee accepted that 34,000 Bidoon are meeting the eligibility requirements for Kuwaiti citizenship[footnote 22]. 68,000 Bidoon are said to be Iraqi citizens or have ‘other origins’, and have 3 years to correct their status or face legal action. A further 4,000 individuals are recorded as status unknown[footnote 23].

2011 – February – Bidoon community began protesting peacefully, demanding to be recognised as citizens of Kuwait. The security forces used force to disperse demonstrations and arrested protesters[footnote 24].

2014 – February/March – Authorities used tear gas and rubber bullets to halt demonstrators. Dozens of people arrested with many injured[footnote 25].

2015 – Government officials suggest that Kuwait may ‘solve’ the Bidoon community’s nationality claims by paying the Comoros Islands to grant the Bidun a form of economic citizenship[footnote 26].

2017 – April – The Government announced a new initiative that would allow Bidoon sons of soldiers who were either killed, missing in action, or served in the military for 30 years to be eligible to join the military[footnote 27].

2019 – July – Protests take place following the suicide of 20-year-old Ayed Hamad Moudath after he was reportedly unable to obtain official documentation and as a result lost his job[footnote 28].

2019 – November – New legislation brought up in Kuwait’s Parliament that stated Bidoons could apply for citizenship and be granted residency providing that they declare their original nationalities[footnote 29].

2020 – November – The mandate of the Central System to Resolve Illegal Residents’ Status was extended by another year by the Kuwaiti authorities[footnote 30].

2021 – Bidoons who did not have a security card or whose card had expired, could not register for Covid-19 vaccinations[footnote 31].

2022 – August – Kuwaiti authorities arrested 18 people, including 3 candidates for upcoming parliamentary elections, for taking part in a peaceful demonstration in support of Kuwait’s Bidoon community[footnote 32].

7.2. Location and distinguishing features

7.2.1. The MRG profile on Bidoons stated that ‘Most Bidoon live in slum-like settlements on the outskirts of Kuwait City, Tayma, Sulaibiyya and Ahmadi where they lack adequate housing and protection from Kuwait’s extreme weather conditions.’[footnote 33]

7.2.2. The Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), the French government refugee agency published their report ‘Les Bidoun’ (the OFPRA paper) on 6 September 2019. The information below and from this source, and used elsewhere in this CPIN has been translated from French using Google translate. As such, 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed.– (translation available upon request):

‘There is no physical or clothing element to distinguish the Bidoun from Kuwaiti citizens. The Bidoun are “administratively foreign but share the same ethnic and cultural heritage with nationals,” summarizes researcher Claire Beaugrand[footnote 34], a specialist in the issue of the Bidoun in Kuwait. They speak the same language, with the exception of some dialect intonations. They wear, like all Kuwaiti citizens, a white toga (“dishdasha”) and a scarf (“ghutra”) which they tie on their heads with a black rope (“iqal”).’[footnote 35]

CPIT was unable to find further information about the differences in dialect between Kuwaiti and Bidoons however this may be due to differences in education.

7.2.3. The OFPRA paper added ‘The Bidoun mainly reside on the outskirts of Kuwait City, in the towns of Tayma, Sulaibiyya, Ahmadi or Al-Jahra.’[footnote 36]

7.2.4. In March 2024, following a request for information by CPIT regarding Bidoons, Dr Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, the Fellow for the Middle East at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy[footnote 37] stated that:

‘Many Bidoon live in slum-like settlements, often on the outskirts of Kuwait City, especially in the neighbourhoods of Tayma, Sulaibiyya, and Ahmadi, and in substandard housing. They are largely segregated from most Kuwaitis who do not live in such neighbourhoods (they are far more likely to live among communities of migrant, i.e. non-Kuwaiti workers). Kuwaiti citizens are generally able to identify by accents and aspects of dress elements of an individual’s background that likely would identify them as Bidoon.‘[footnote 38]

7.2.5. In April 2024, following a request for information by CPIT regarding Bidoons, Dr Claire Beaugrand, a lecturer at the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies at Exeter University[footnote 39] stated: ‘Distinguishing between a Kuwaiti citizen and a Bidoon is impossible – apart from situations where the social acceptance excludes the possibility of the person being a Kuwaiti, for instance for street sellers who would never be Kuwaitis.

7.2.6. She added

‘There have historically been areas where Bidoons live, in what is called “popular housing” areas, in South Ahmadi, Tayma (Jahra) and Sulaybiyya. These housings were linked to their employment in the police and armed forces.

‘Yet even at the time when popular housings were built, some Bidoons, in other employment, were living outside of these areas.

‘I noted in my book[footnote 40]: “As a result, the new generations have left the popular housing to rent in lower-class expatriate areas like Farwaniyya, Jlib al Shuyukh, Sabah al Salim and further south on the road towards Ahmadi.

They joined the other biduns, who never benefited from the state housing of the armed forces, around Umm al Hayman and in any other affordable accommodation (Khaitan, Hawalli).”’[footnote 41]

7.2.7. In April 2024, following a request for information by CPIT regarding Bidoons, the UK Foreign Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) stated that: ‘[Bidoons live in] Shanty towns on outskirts of Kuwait City, Tayma, Sulaibiyya and Ahmadi. Those who find employment may live in Bayan, Salmiya and Mahboula but this is dependent on finding a willing landlord)’[footnote 42]

7.2.8. The below map, created by CPIT in May 2024, shows the locations of where Bidoons are predominantly found in Kuwait according to the sources in the paragraphs above:

7.2.9. The FCDO additionally stated ‘[The] Vast majority [of Bidoons] are Sunni.’[footnote 43]

7.2.10. Dr Beaugrand explained that ‘… Bidoon are said to be mostly Shiites and in my view, the majority of them probably is. Yet I met Sunni Bidoons when I was carrying fieldwork in Kuwait. In the absence of figures, it is difficult to have a precise idea of the religious composition of the group.’[footnote 44]

7.2.11. It should be noted that sources differ on whether the Bidoon are predominantly Shia or Sunni Muslims. CPIT was unable to find further information on this topic within the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

7.3. Population

7.3.1. Salam for Democracy and Human Rights (SDHR) is a human rights NGO undertaking research and advocacy on statelessness in the Gulf and wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region[footnote 45]. Their report entitled ‘The Bidoon in Kuwait, History at a Glance’ from October 2020 stated:

‘In several countries of the Gulf there are stateless persons referred to as the Bidoon… The most prominent case is in Kuwait where there is a particularly large Bidoon population, often estimated at around 100,000 – 120,000… According to official Kuwaiti estimates, there were some 4.4 million people living in the country in 2019, of whom 1.3 million – just short of 30% – were Kuwaiti nationals. Even if one accepts the lower estimate of the Bidoon population (100,000 persons) this would equal just under 8% of Kuwaiti nationals.’[footnote 46]

7.3.2. The United States Department of State (USSD) report for human rights practices in Kuwait, covering events in 2023 and published in April 2024 stated (repeated from previous years):

‘UNHCR estimated there were 83,000 stateless persons in the country, mostly Bidoon residents considered illegal residents by authorities and denied citizenship. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and international and local media estimated the Bidoon resident population was more than 100,000, while the government reported the Bidoon population was approximately 83,000, based on those who held Central Agency identity cards.‘[footnote 47]

The source does not provide further evidence of the Kuwaiti government source or how it arrived at the figure of 83,000. Whilst it may be possible to extrapolate that 83,000 Bidoon hold identity cards (Review cards), the source does not explicitly say that 83,000 Bidoon hold cards. No further information on the number of Bidoon holding review cards can be found by CPIT within the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

7.3.3. A briefing paper on Bidoons produced by the FCDO in October 2023 (see Annex A) stated: ‘According to Kuwait official estimates, there were, at a peak pre-1990, c. 220,000 [Bidoons] in country, and around 85,000 as of 2018. These figures remain contested by Amnesty International, who claim there are approximately 100,000 Bidoon currently in Kuwait.’[footnote 48]

8. Kuwait’s Nationality Law

8.1. The 1959 Nationality Law

8.1.1. Kuwaiti nationality is determined by Kuwait’s 1959 Nationality Law. The main relevant provisions are:

- Article 1 – those who were settled in Kuwait prior to 1920 and who maintained their normal residence there until the date of the publication of the Law;

- Article 2 – those born in, or outside, Kuwait whose father is a Kuwaiti national;

- Article 3 – those born in Kuwait whose parents are unknown;

- Article 4 – Kuwaiti nationality may be granted by Decree upon the recommendation of the Minister of the Interior to those proficient in Arabic who could prove their lawful residence in Kuwait for 15 years for Arabs or 20 years for non Arabs[footnote 49].

8.1.2. The MRG profile on Bidoons stated ‘Children of Bidoon parents do not have any claim to citizenship, despite being born in Kuwait. Moreover, children born to Kuwaiti mothers and Bidoon fathers are also considered Bidoon, except in cases of divorce or death of the father.’[footnote 50]

8.1.3. Dr Susan Kennedy Nour al Deen, a Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Adelaide with an interest in statelessness and citizenship[footnote 51], in her October 2016 Doctoral Thesis entitled ‘The Stateless Bedoun in Kuwait Society. A study of Bedouin Identity, Culture and the Growth of an Intellectual Ideal’ stated: ‘[T]hose who served in the police or armed forces were qualified to receive citizenship due to their service to the nation, in Article 4, paragraph 4 of the Nationality Law 1959.’[footnote 52]

8.1.4. A previous iteration of the USSD human rights report for Kuwait, covering events in 2022 and published in March 2023 (information not included in the latest 2023 report) stated that ‘The government often granted citizenship to orphaned or abandoned infants, including Bidoon infants.’[footnote 53]

8.1.5. The October 2023 FCDO briefing paper on Bidoons (Annex A) stated: ‘The citizenship awards process set out in the Nationality Law of 1959 is… unclear… as it does not allow the Bidoon to provide any evidence to support their case for naturalisation. The provisions of the law – that authorises executive naturalisation (after birth) – requires the individual to be proposed for citizenship, on a discretionary basis, by the Ministry of Interior (MOI) and cannot exceed the legal quota 4,000-naturalisation p.a. [per annum].’[footnote 54]

8.2. Implementation of the law

8.2.1. The undated MRG profile on Bidoons stated:

‘There has been little progress on naturalization, despite repeated promises. A law passed in 2000 permitted the naturalization of Bidoon and their descendants, provided they could show that they were registered in the 1965 census, thereby proving that they were in the country at the time of independence. However, it has been reported that only a small number of Bidoon were able to acquire nationality through this process, and these were predominately those with wealth or connections’[footnote 55]

8.2.2. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung (RLS) a Geneva based human rights association[footnote 56], stated in their article ‘Kuwait: Just wanting to belong’ published on 18 January 2021 that: ‘The Emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad al- Sabah, issued a decree in 1999 that makes the naturalization of 2,000 Bidoon per year possible. However, research by the portal Inside Arabia shows that only three percent of the Bidoon in Kuwait had received citizenship by 2019.’[footnote 57]

8.2.3. A previous iteration of the USSD human rights report covering events in Kuwait in 2021, published 12 April 2022, (information not included in the latest 2023 report) stated: ‘According to international observers, some Bidoon residents underwent DNA testing purportedly to “prove” their Kuwaiti nationality by virtue of blood relation to a citizen. Bidoon residents are required to submit DNA samples confirming paternity to become naturalized, a practice critics said leaves them vulnerable to denial of citizenship based on DNA testing.’[footnote 58]

CPIT was unable to find any further evidence regarding Bidoons undergoing DNA testing in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

9. State attitudes towards Bidoons

9.1.1. The MRG profile on Bidoons stated: ‘The overall attitude of the Kuwaiti authorities to Bidoon has changed very little since the 1990s. The government has asserted that Bidoon enjoy human rights on an equal basis with nationals of Kuwait but it continues to refer to Bidoon as illegal residents, and paints them as opportunistic foreign nationals who have destroyed their original documents in order to stay in Kuwait and take advantage of the provisions of the welfare state.’[footnote 59]

9.1.2. In the response of Kuwait to Concluding Observations of the UN Human Rights Committee (UNHRC), filed on 27 April 2017, which sought to encourage Kuwait to resolve the Bidoon situation positively, the Government of Kuwait responded inter alia to the recommendation of the UNHRC that it increase regularisation of status of the Bidoon and guarantee their human rights by stating as follows:

‘1. It should first be emphasized that there are no so-called “stateless persons” or “Bidoon” in the State of Kuwait, since these terms refer to persons who have no nationality. This is not applicable to the status and concept of illegal residents, who entered Kuwait illegally and concealed the documents indicating their original nationalities owing to their aspiration to acquire Kuwaiti citizenship and its associated benefits.

‘2. They are officially designated “illegal residents” pursuant to Decree No. 467/2010 concerning the establishment of the Central Agency.

‘3. The granting of Kuwaiti citizenship is a sovereign matter that the State assesses in accordance with its best interests. It is subject to the conditions and regulations laid down in the Kuwaiti Nationality Act No. 15/1959, as amended, which specifies the cases in which the possibility of granting citizenship may be considered. The Central Agency for Regularization of the Status of Illegal Residents [see Central Agency for Remedying Illegal Residents’ Status (CARIRS)] examines, investigates and scrutinizes the situation of such persons on a case-by-case basis, in full transparency and without succumbing to pressure or personal whims, in accordance with the road map produced by the Supreme Council for Planning and Development, approved by the Council of Ministers and promulgated by Amiri Decree No. 1612/2010.

‘… 14. If the idea is that the State should apply the provisions of these Conventions to illegal residents, we wish to point out that many international human rights organizations confuse the terms “stateless” and “illegal residents”, although there is an enormous difference between them in both conceptual and legal terms.

‘… 15. In conceptual terms, “stateless persons” are persons who are not recognized as citizens under the law of any State, in other words persons without a nationality of their own. This is inconsistent with the concept of “illegal residents”, since these are persons who entered Kuwait illegally and concealed the documents indicating their original nationalities owing to their aspiration to acquire Kuwaiti citizenship and its associated benefits.’[^60}

9.1.3. The USSD report for covering events in 2023, published in April 2024 stated that ‘The government alleged most Bidoon residents concealed their “true” nationalities and were not stateless. Central Agency officials offered incentives to Bidoon who declared an alternate nationality, including priority employment and the ability to obtain a driver’s license.’[footnote 61]

9.1.4. The October 2023 FCDO briefing paper on Bidoons (Annex A) in relation to proposed laws regarding Bidoons and Kuwaiti nationality stated:

‘In 2020, the National Assembly Speaker Marzouq Al-Ghanim proposed a law that would incentivise the Bidoon to abandon long-standing claims to Kuwaiti nationality in exchange for short-term economic gain. However, it was not passed. The draft would have given the Bidoon community one year to register with the Central Agency and correct their legal status before they would be treated as “foreigners in violation of the law” and declared ineligible for future acquisition of nationality, placing severe pressure on Bidoon to ‘admit’ to holding a non-Kuwaiti nationality and surrender their claim to Kuwaiti nationality. The Bidoon community were extremely hostile to this law, and questioned whether those who accepted a non-Kuwaiti nationality would face deportation following a proposed 15-year grace period which they would be afforded ‘privileged resident’ status in addition to having access to free healthcare, education and subsidised food, among other benefits. The proposal did not pass in the National Assembly.

‘… A second proposal by the Kuwaiti Lawyers’ Association sought to address issue in a more humane manner and redefine the Bidoon as “Residents whose nationality has not been recognised”, rather than “Illegal Residents” enabling those coerced into “recognising” their non-Kuwaiti nationality to return to their previous legal status. The proposal outlined access to education & healthcare and the abolishment of the Central Agency. Though this law would not have granted nationality to all stateless persons in Kuwait, and not a comprehensive solution, it laid out a plan for naturalisation that would have benefited many of the Bidoon and granted all other stateless persons in Kuwait permanent residence and access to essential services. This proposal also failed to gain enough support to pass.’[footnote 62]

10. State apparatus regarding Bidoons

10.1. Overview

10.1.1. The SDHR report published in October 2020, citing various sources[footnote 63], stated:

‘After the war [between Kuwait and Iraq] a series of committees were established to register the population, ostensibly to get a clearer view of the country’s demographics, for example the 1991 Committee to Register Foreigners… A specific process was then initiated with regards to the Bidoon. In 1993 the Central Committee… was set up tasked with studying the situation of the Bidoon in Kuwait.

‘…This committee was in turn replaced in 1996 by the Executive Committee for the Affairs of Illegal Residents… with the aim of implementing decisions on the basis of the findings of the 1993 committee. It demanded the Bidoon to register their claims of nationality between 1996-2000. Those who registered were given a ‘review card’ [see Review Card]… , which was only valid for transactions between the Bidoon card holder and Kuwaiti authorities. As with the nationality registrations in 1959-1965, some Bidoon did not or were again unable to register with the committee. The Kuwaiti government itself released information that 12,000 individuals had not opened files with the Kuwaiti authorities.

‘… Even so, many Bidoon did register; according to the Kuwaiti authorities’ own figures some 106,000 had registered in the four-year period from 1996. However, the Kuwaiti Supreme Court of Higher Planning determined that of these 106,000 registrations, only 34,000 were potentially eligible for citizenship, 68,000 had other origins (42,000 “already Iraqis” and 26,000

“Other” known origins), and the remaining 4,000 were “unknown”. Many Bidoon dispute these official “findings”, especially as in some cases members of the same family have been “found” to have different national origins.

‘… There is no appeals process to deal with such issues, which essentially bar the registered Bidoon from being considered for nationality. In other cases, many who have registered have found a “security restriction”… on their file, preventing them from being considered for nationality or even requesting basic documents or services that, in principle, should be granted [to] Bidoon who have registered with the authorities.

‘In 2010 a third special committee was established that would continue processing these registrations. The Central System for Remedying the Status of Illegal Residents… remains the body which deals with Bidoon matters and, ostensibly, investigates the origins of the registered Bidoons.’[footnote 64]

10.1.2. Dr Claire Beaugrand stated in April 2024:

‘[S]ince 1993 a special government unit under the Ministry of the Interior has been in charge of dealing specifically with the files of the biduns. From 1993 to 1996, the Central Committee (Lajnat markaziyya) was tasked with registering, regularising and overseeing bidun affairs. Established in 1996 by the Ministry of the Interior and based in ’Ardiyya, the Executive Committee for the Affairs of Illegal Residents (Lajnat tanfiziyya li shu’un al muqimin bi- sura ghayrqanuniyya) – shortened as Executive Committee, took over from the Central Committee.” Since that time, the Kuwaiti authorities keep data on the majority of the Bidoons residing on its territory.’[footnote 65]

10.2. Central Agency for Remedying Illegal Residents’ Status (CARIRS)

10.2.1. The Central Agency/System is referred to by a number of different names in the sources below. It is also abbreviated to CARIRS (The Central Agency for the Remedy of the Situation of Illegal Residents).

10.2.2. On 24 August 2020 Landinfo, the Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, published a query response, citing various sources[footnote 66], entitled ‘Kuwait: The Bidun’s review cards’ which stated:

‘The current committee, the Central System – Central System to Resolve Illegal Residents’ Status – has more extensive powers than its predecessors. Referred to as “a state within the state”, the Central System regulates the Biduns’ access to documents and formal rights in an arbitrary and non- transparent manner. Biduns do not have insight into the basis of the committee’s decisions, nor can they contest the decisions. In practice, the courts also lack authority to rule on the status of stateless persons.

‘According to the Central System itself, the Bidun files are categorised in three groups (Central Agency 2017):

‘1. Illegal residents whose status need to be adjusted.

‘2. Illegal residents who might be considered for naturalization.

‘3. Illegal residents for whom residency permits are issued after remedying their status (i.e. after declaring their original nationality).

‘Biduns registered with the Central System are to be issued with a card confirming their registration, a so-called review card (also known as a security card) [see Review card]. The card contains the holder’s personal data and a case number but is not a regular ID card.’[footnote 67]

10.2.3. A previous iteration of the USSD report that covered events in 2022 and was published in March 2023 stated:

‘The Central Agency for Illegal Residents oversees Bidoon resident affairs. In 2021, the Council of Ministers issued two resolutions that extended the agency’s expired term by two additional years and reappointed the head of the agency. Bidoon residents, Bidoon rights advocates, members of parliament, and human rights activists protested the decision, arguing that the agency had not been effective in resolving matters pertaining to the Bidoon, and that conditions for Bidoon residents had dramatically deteriorated under the agency’s leadership… The Central Agency received tens of thousands of citizenship requests by Bidoon residents for review since its establishment in 2010. Data on the number of requests accepted by the Central Agency was unavailable.’[footnote 68]

10.2.4. The same source additionally stated:

‘In February [2022], the Central Agency announced that 18,217 Bidoon “revealed” their true nationalities from 2011 to 2021. The Central Agency indicated that of these individuals, 8,068 persons claimed Iraqi nationality, 6,583 claimed Saudi nationality, 309 claimed to Iranian nationality, 115 claimed Jordanian nationality, and 2,009 claimed other nationalities. The Central Agency stated it was currently following up on 9,090 additional cases for which it had identified other nationalities.’[footnote 69]

10.2.5. The October 2023 FCDO briefing paper on Bidoons (Annex A) stated: ‘In 2010, the Government created an agency tasked with resolving the Bidoon issue: CARIRS [The Central Agency for the Remedy of the Situation of Illegal Residents]. However, it has been criticised for creating more roadblocks and hardships for Bidoon rather than improving their situation. In October 2022, the Agency released figures stating that between 2011 and 2022, 18,227 individuals had completed the process of obtaining nationality. However, we understand that none were given Kuwaiti nationality, and there is little explanation of how nationalities were allocated. There have been no guarantees that these new nationalities would be validated by the corresponding country, and no clarity on the changes in rights and status for these individuals in Kuwait.’[footnote 70]

10.2.6. Further information on the number of Review cards issued by the Kuwaiti authorities could not be found in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

10.3. Revocation of (and difficulties faced when attempting to obtain) citizenship

10.3.1. The MRG profile on Bidoons stated:

‘Many Bidoon opted to purchase fake foreign passports from offices that sprung up all over the country in the 1990s [in order to regularize their status and qualify for legal work permits], a process that appears to have taken place with the knowledge and even the encouragement of the Kuwaiti government. Many found that their possession of a foreign passport, even an illegitimate one, was later used to undermine their claims for Kuwaiti nationality.’[footnote 71]

10.3.2. Dr Susan Kennedy Nour Al Deen’s Doctoral thesis from 2016, stated the following regarding a Bidoon interviewee who had been granted citizenship:

‘In the case of the interviewee granted citizenship, his whole family unit was subjected to exploitative treatment during the administrative processes required to change his identity from “non-Kuwaiti” to “Kuwaiti”. The process took many years to complete and involved the isolation and interrogation of different sections of the family. The strategy of intimidation appeared to be deployed in an attempt to coerce the family into giving up on the process before each member had their citizenship grant finalised.’[footnote 72]

10.3.3. The same source additionally that ‘Another part of the [the Central System] program was developed within the Ministry of Defence, which involved thousands of Bedoun servicemen, who were forced to sign affidavits claiming they were nationals of other countries. They had previously held Kuwaiti national passports, issued to them because they performed their military roles in Kuwait and overseas.’[footnote 73]

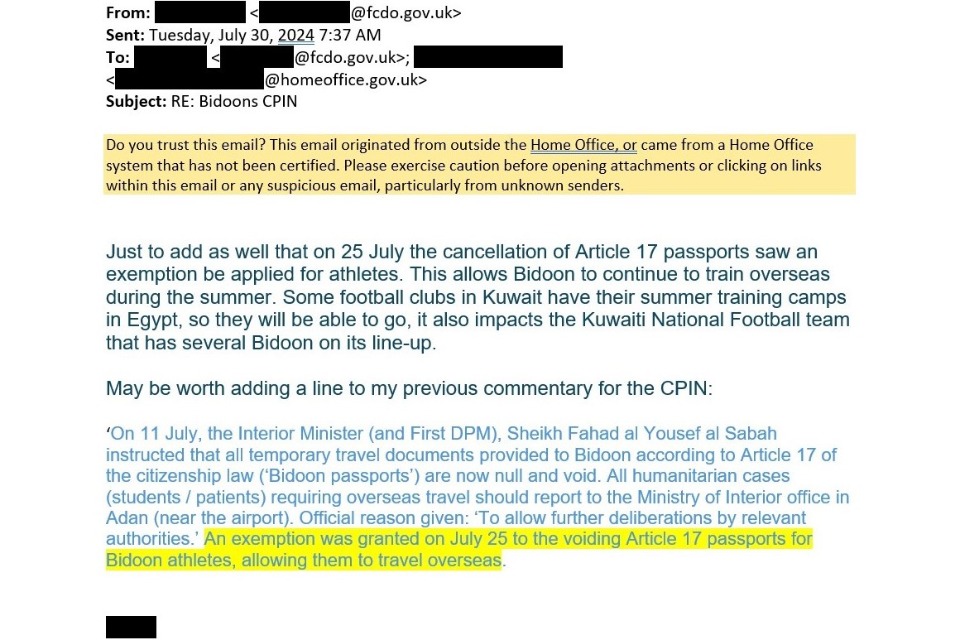

CPIT could not find any information on Bidoon members of the armed services having held Kuwaiti passports within the sources consulted (see Bibliography), it can be presumed the author is referring to Article 17 travel documents.

10.3.4. The European Network on Statelessness (ENS) and the Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion (INS) published a paper in May 2019 citing various sources[footnote 74] which stated:

‘The grounds on which an individual may be deprived of Kuwaiti nationality differ between those who are naturalised citizens (Article 13) and those who are citizens by birth (Article 14). They include grounds relating to fraud, loyalty and other forms of behaviour, including some broadly formulated powers such as where a person “disseminated opinions which may tend seriously to undermine the economic or social structure of the state”.

‘… Since 2011 there has been increased denationalisation in Kuwait, because of a crackdown on dissent after the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ which led to increased protest. There are no comprehensive figures on how many people have been stripped of their nationality, but the number is believed to be in the hundreds. The US State Department reported that: “A Council of Ministers committee created in 2017 to review citizenship revocations since 1991, received 200 appeals and sent their recommendations for 70 of those to the Council of Ministers. Seven families had their citizenship restored, while the other 63 were rejected”. It has been reported that Kuwaiti children have had their nationality revoked as a consequence of their parents having their nationality revoked.’[footnote 75]

10.3.5. Bertelsmann Stiftung (BTI), a social change non-profit foundation[footnote 76] in their 2022 Country report for Kuwait, published 23 February 2022 stated that ‘As a consequence of growing social contestation following the Arab upheavals in 2011, the government has frequently stripped critics of their citizenship. This form of repression – meant to silence dissidents – peaked in 2014 but has decreased since then.’[footnote 77][see Bidoon protests and treatment of activists]

10.3.6. A previous iteration of the USSD report for 2022, published March 2023, said

‘By law the government is prohibited from revoking the citizenship of those born a citizen unless an individual takes a second nationality. The government can revoke the citizenship of naturalized citizens for cause and can subsequently deport them. Justifications for such revocations include felony conviction for “honor-related and honesty-related crimes,” obtaining citizenship dishonestly, and threatening to “undermine the economic or social structure of the country.”

‘… On occasion the government revokes citizenship. The Supreme Committee for the Verification of Kuwaiti Citizenship reported that as of October, it had naturalized 12 persons and revoked the citizenship of six citizens. If a person loses citizenship, all family members whose status was derived from that person also lose their citizenship and all associated rights. Absent holding another nationality, those impacted would become stateless. Authorities can seize the passports and civil identification cards of persons who lose their citizenship and enter a “block” on their names in government databases. This “block” prevents former citizens from traveling with Kuwaiti passports, accessing free health care, or using other government services reserved for citizens… The government may deny a citizenship application based on security or criminal violations committed by the individual’s family members.’[footnote 78]

10.3.7. The USSD report for 2023, published April 2024 stated:

‘Bidoon leaders alleged that when some members of the Bidoon community attempted to obtain government services from the Central Agency, officials required Bidoon individuals to sign a blank piece of paper to receive the necessary paperwork. Later, Bidoon activists reported the agency would write a letter on the signed paper purportedly stating they held another nationality.

‘The Central Agency operated an electronic renewal service for security cards on its website, as well as online services including health insurance, marriage, divorce, and inheritance certificates. Bidoon reported that while they were able to obtain an electronic security card, the Central Agency still required them to sign a blank paper prior to receiving the card.’[footnote 79]

10.3.8. In March 2024, Dr Kristian Coates Ulrichsen stated:

‘Security restrictions may include participating in unauthorized demonstrations or criticizing the government on social media, as well as using fake passports to acquire five-year resident visas to work in Kuwait. Another common reason for rejection is the suspicion that the Bidoon has a foreign nationality; here, too, there are reports that individual applicants may be affected by family members who have acquired (voluntarily or otherwise) another nationality, and themselves be deemed to be foreign. It is not clear how many applications are approved or denied or that any such data is made public and/or accessible.

‘… If Bidoons accept another nationality and present a passport from another state, they can usually obtain a five-year residence visa to work in Kuwait, but a problem many face is that the passports they obtain are fake and non-renewable, which makes it difficult (if not impossible) to renew the visas.’[footnote 80]

10.3.9. In April 2024, following a request for information by CPIT regarding Bidoons, Dr Claire Beaugrand stated:

‘I never came across a Bidoon being deported recently. I documented the case of Ahmed al Muhri in 1979 whose father was de-naturalised and as a consequence the 19 members of the family deported to Iran but this has not happened in the case of the 2014 denaturalisations (later reversed).

‘My understanding is that the foreign nationalities written on the cards of the Bidoons are not recognised by the other state of which the Bidoon is said to be a national.’[footnote 81]

10.3.10. In April 2024, the FCDO, when asked how likely it is that a Bidoon renewing a review card would be pressured into accepting a nationality other than Kuwaiti, stated that: ‘Review cards are essentially doing that by default. The review card states clearly the holder is non-Kuwaiti, either undefined or named other nationality (but not officially recognised by the ‘home country’).’[footnote 82]

10.4. Appealing denied Kuwaiti citizenship

10.4.1. The USSD report covering events in 2022 stated ‘The Court of Cassation has ruled that decisions issued by the Central Agency for Illegal Residents fall under the jurisdiction of the judiciary and as a result, are challengeable in the courts, excluding those related to citizenship status.’[footnote 83]

10.4.2. Amnesty International’s (AI) report entitled ‘“I don’t have a future”: Stateless Kuwaitis and the right to education’ from 17 August 2023 stated ‘In April 2022, Kuwait’s Court of Cassation ruled that courts may not consider questions of nationality at all, as these are solely the province of the executive branch. With this decision, Bidun residents have been decisively blocked from seeking to redress their statelessness and acquire Kuwaiti nationality through the judicial system, just as they have been blocked by executive policy for decades’[footnote 84]

10.4.3. The October 2023 FCDO briefing paper on Bidoons (Annex A) stated that ‘In April 2022, the Court of Cassation – Kuwait’s highest judicial non- constitutional authority – ruled that all matters of nationality fall exclusively under executive jurisdiction, leaving no alternative pathway to naturalisation.’[footnote 85]

10.4.4. The USSD report covering events in 2023, published in April 2024 stated that ‘The law did not provide stateless persons, including Bidoon, a clear path to acquire citizenship. The law did not give the judicial system authority to rule on the status of Bidoon, leaving Bidoon with no avenue to present evidence and plead their case for citizenship.’[footnote 86]

10.4.5. In April 2024, Dr Claire Beaugrand stated ‘My understanding is that Bidoons, as illegal residents, have an extremely limited access to the judiciary. Because of their vulnerable situation they would need to be backed by powerful Kuwaiti nationals. This is certainly the case when they appeal against decisions that regard them.’

‘…My experience is that holders of files for naturalisation (for instance children of widowed or divorced Kuwaiti women, legally eligible to nationality) wait for years until the Supreme Committee and Cabinet approve their demand. The absolute sovereignty of the executive in nationality matters is particularly applicable with respect to the Bidoons’ claim to nationality[footnote 87]

11. Documentation

11.1. Review card

11.1.1. Although commonly referred to as ‘security card’, the Kuwaiti government refers to these documents as ‘review cards’. The sources referenced in this section present conflicting accounts regarding review cards. Discrepancies include the colours of these cards, what each colour card means or entitles the holder to and their validity periods. However, among these sources, yellow emerges as the most frequently cited colour for these cards.

11.1.2. In an undated response to a letter from HRW in May 2011 the Kuwaiti Government stated:

‘Firstly, the term used in your report – “security card” – is not accurate. The proper official term is “review card.” Under Decree 482/1996, amended by Decree 49/2010, a card is issued to every person over the age of five who has a file with the Central System to Resolve Illegal Residents’ Status. The review card contains a personal photo, place of residence, civil number, file number, date of birth, date of its issuance, and an expiration date. There are two types:

‘The first type: Its duration is two years and it is issued to those registered in the 1965 census or those who have proof of long-term residence in the country from that year or prior to it.

‘The second type: Its duration is one year and is issued to the remaining groups who are not registered in the 1965 census and do not have proof of long-term residence from that year or prior to it.’[footnote 88]

CPIT could not find further current information on the two types of review card and this source may be referring to the old form of review card issued pre- 2012

11.1.3. In June 2017, Lifos, the Swedish Migration Agency’s institution for legal and country of origin information, published an article entitled ‘“Bidooner” I

Kuwait’. The report contained an interview with the Regional Immigration Liaison Manager at the British Embassy in Doha, Qatar on the 26 April 2017 who stated the following regarding different types of review card (the information below has been translated from Swedish using Google translate. As such, 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed – translation available upon request):

‘1. Yellow card (with yellow strip at the top) – issued to the majority of the Bidoons.

‘2. Blue card – issued to people where the central system was located documentation indicating that they basically have a different nationality, for example Iraqi, Iranian, Saudi or Syrian (usually referring to found documentation regarding ancestors). This category are said to be able to legalize their status if they apply for documents at basis of the nationality that emerged. The validity period is six months, and can be extended for another six months in the meantime the nationality is processed and possibly determined. To encourage this procedure provides the person in question with certain benefits and the possibility of “sponsoring” oneself for a five-year residence permit. Blue cards are also issued to children of a Kuwaiti mother.

‘3. Green card – issued (theoretically) to persons covered by 1965 year’s census and whose dossier was ready for decision on Kuwaiti citizenship. Reportedly, these cards never have issued.

‘4. Red card – issued (theoretically) to people appearing in criminal record or with security restrictions. Reportedly have nor were these cards issued.’[footnote 89]

CPIT has been unable to find any further information on blue review cards in the sources consulted (see Bibliography).

11.1.4. The OFPRA paper stated (the information below has been translated from French using Google translate. As such, 100% accuracy cannot be guaranteed – translation available upon request)

‘[E]ach person who registers with the agency responsible for resolving the status of illegal residents is assigned an identification card (in English, “review card”). These cards are colour coded. A green card means that its holder is eligible for naturalization. A yellow card means that its holder can obtain regularisation under another nationality that he holds or for which he is eligible. A red identification card means that its holder is excluded from the naturalization process because of his criminal record or because he does not have proof of his residence in Kuwait before 1980.

‘According to statistical information collected by Claire Beaugrand with the agency in charge of resolving the status of illegal residents [in 2018], among the 105,702 files identified, 34,000 [32%] people were designated eligible to obtain a nationality, 900 [0.8%] people were excluded from the naturalization process in because of their criminal record and 8,000 [7.5%] because they do not have proof of residence in Kuwait before 1980. The rest of the applicants (around 62,800 [59%] files) are not, according to the agency, stateless, but in reality holders or eligible for a nationality other than Kuwaiti nationality. They are therefore invited to regularize their situation on the basis of their other nationality.’[footnote 90]

11.1.5. However, there is conflicting information on the renewal period of review cards and Landinfo query response from 24 August 2020 stated that: ‘A well- informed source informs to have seen yellow cards valid for one year in 2014 and has never seen green cards issued after 2011…In the opinion of the well-informed source, the colour-coded card system no longer seems relevant. Most cards issued now are reportedly yellow, showing that the holder is asked to regularise his/her basis for residence…’[footnote 91]

11.1.6. The following is an image from Claire Beaugrand’s paper ‘The Absurd Injunction to Not Belong and the Bidūn in Kuwait’ from December 2020 translated using google translate.

11.1.7. Dr Susan Kennedy Nour Al Deen’s Doctoral thesis from 2016, included the following image (front and back) of the old form of review card (pre-2012):

11.1.8. Roswitha Badry from the University of Freiburg Germany[footnote 94] in her article

‘When the Subalterns find their Voice – The Example of Kuwait’s Bidun’ from 2021 noted:

‘The introduction of colour-coded “reference (review) cards”… in 2012 presented a new stigmatizing and discriminating effort and was accompanied by a governmental framing of Bidun as enemies of the state, playing the card of sectarianization and securitization. The coloured cards reflect the holders’ legal status and are not valid as identity cards, but essential for getting access to basic services; they are often referred to as “security cards” because the holders’ legal status is fluid. These cards do not cover unregistered Bidun (about 12,000 persons, or circa 10%, according to official sources).’ [footnote 95]

It is not clear what official sources Roswitha Badry refers to that references this statistic.

11.1.9. The same source stated:

‘… The majority of Bidun have a yellow card, which means their status is “under review”. The holders of a green card (34,000 persons according to official data) are said to have the best chances to be naturalized, while those with the red card have none, either due to the lack of the required documents or a criminal record. Since the Bidun protests started, the number of Bidun individuals with “security blocks” against them has greatly increased.’[footnote 96]

11.1.10. The Diplomatic Service of the European Union (EEAS) in their EU Annual Report on Human Rights and Democracy in the World 2022 Country updates, published 31 July 2023 stated:

‘The stateless “Bidoons” continued to face significant challenges in securing identification documents (“security card”), indispensable to access basic services in healthcare and education. The “Central Agency for the Remedy of the Situation of Illegal Residents” was often accused by “Bidoon” activists of forcing them to claim a third nationality, without actual connection to the country, in order to issue/renew security cards.’[footnote 97] (see Revocation of (and difficulties faced when attempting to obtain) citizenship

11.1.11. AI’s 2023 report stated:

‘The Civil Identity card bearing the Civil Identity Number is a primary form of identification in Kuwait and, unless a special exception is made, is required by law for government transactions, bank services, employment, school and university registration and membership in organizations.

‘… The Review Card can be obtained by those who have the finalized Ministry of Health birth certificate and Civil Identity Number, but not by those who have only the simple hospital report of the birth.

‘… The frequent changes in the kinds of documentation required of Bidun and to government rules affecting their access to education and other public services, create significant socio-economic instability and hardship for Bidun people in Kuwait.

‘… The existence of so many different kinds of identity document, statuses and categories, subject to frequent change, and the lack of transparency about entitlements to state services, the rules of which also change frequently, creates uncertainty and socio-economic anxiety in the Bidun community. “Lack of stability” is the greatest challenge of being stateless.’[footnote 98]

11.1.12. The same source additionally stated:

‘Bidun persons have their legal existence registered at different levels of formality and official recognition, which vary according to personal and family circumstances. The requirements for Bidun people to have the highest level of personal legal documentation are that:

- their parents were regarded as legally present “illegal residents” at the time of their birth;

- they have applied for the Central System Review Card and renewed it every time it expired (the periods vary – Amnesty International has seen cards with both a six-month and a one-year validity); and

- they have a finalized birth certificate issued by the Ministry of Health, a Civil Identity Number and a currently valid Review Card (without any recorded “reservations” or assigned nationality).

‘Certain classes of Bidun are granted exceptional higher privileges than the Bidun population at large. These are primarily Bidun children whose mothers are Kuwaiti nationals, and Bidun families with fathers or grandfathers who served or are serving in the military or police (without having been dismissed, as many were, at the end of the 1990–1991 Gulf War).

‘The level below, in terms of identity documentation and entitlements, comprises Bidun who obtained a Central System Review Card at some point after 2010, but whose card has expired either because the person refused to sign for receipt of a card that includes Central System-imposed changes to their nationality status, or because they are afraid the Central System will make such changes if they renew their card and so do not apply. The Central System card (when currently valid), like previous kinds of identity documents issued by other agencies before 2010, also grants the bearer status as legally present in the country, despite the government’s overall labelling of the Bidun population as “illegal residents”.

‘The next level below includes those who have never held a Review Card, either because they never registered with the Central System or because they are children born to parents with expired Review Cards. At a lower level, a Bidun person may only have a report of their birth from the hospital in Kuwait where they were born.’[footnote 99]

11.1.13. In March 2024, Dr Kristian Coates Ulrichsen stated:

‘A Kuwaiti birth certificate and Civil Identity Number is required to obtain a review card – a hospital report of birth is not by itself sufficient.’

‘There have been reports in the past of a colour code system, but it is not clear whether this in fact was instituted (a decade ago), still less maintained. There are conflicting accounts of whether the colour coding was related to the length of validity of the card (green for 5 years, yellow for 3 years, red for 1 year) or to status and eligibility (green for eligible for naturalisation, yellow for requests to regularise status, and red for disqualification from eligibility for naturalization based on having a criminal record). It appears that whereas the cards were green in colour until 2012, they are now yellow.’[footnote 100]

11.1.14. In April 2024, Dr Claire Beaugrand stated:

‘In 2011, when the Kuwait authorities announced 11 facilities, they announced a scheme where there will be three different types of cards with a colour code (red/yellow/green). Yet until now, I have only seen “yellow” cards. The cards have a yellow band at its top with the logo of the Central System on the left, that of the state of Kuwait on the right and the words in Arabic “the Central System for the Remedy of the Situations of the Illegal Residents” in the middle. Overleaf, on the yellow band is the “civil number” and the mention: this card is not considered an ID and [should be] used only for its intended purpose. I have seen this mentioned at the bottom of cards as well.’[footnote 101]

11.1.15. In April 2024, the USCIS stated:

‘The color code system for Bidoon Review cards started in 2012. The Review Card colors are as follows:

- Red: For applicants who must settle their status within a year of issuing the card; issued for those within the 1980 census or later. Holders of this card are eligible for only two government services: Public education and healthcare.

- Green: For those whose status may be prioritized for review of citizenship eligibility. The card is valid for 5 years. The individuals must prove they were part of the 1965 census.

- Yellow of 2012: For individuals permitted legal residency for up to 3 years. For individuals who can show they were present between the years 1966 to 1979. They are excluded from citizenship consideration.

- Yellow of 2015: Valid for only 3 months and is issued for those who have criminal records or security concerns, or to those who can only prove their presence in Kuwait from 1980 to 1985.

- Blue: For those who settled their status and have forged passports. This card is also called “Service Card”.’[footnote 102]

CPIT has been unable to find information on blue ‘service’ cards or information on holders of red cards being eligible for public education and healthcare in the sources consulted (see Bibliography)

11.1.16. In April 2024, the FCDO stated: ‘Officially review cards can be issued for individuals from the age of 5, and last for 5 years. But anecdotal evidence shows this varies, 1-2 years is becoming standard.’[footnote 103]

11.2. Renewal of review cards

11.2.1. The August 2020 Landinfo query response stated: ‘In general… the system is less straightforward than it might seem. The card needs to be renewed frequently, having been issued with an increasingly shorter validity length in recent years. While they were previously valid for one or two years, they are now valid for either three months, six months or a maximum of twelve months. A well-informed source told Landinfo that more and more frequently, the cards are only valid for three months.’[footnote 104]

11.2.2. The same Landinfo response stated: